Leroy Schwarcz, one of the first engineers hired to build SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory’s original 2-mile-long linear accelerator, thought his wife might like to use old mechanical drawings of the project as wrapping paper. So, he brought them home.

His wife, acclaimed enamelist June Schwarcz, had other ideas.

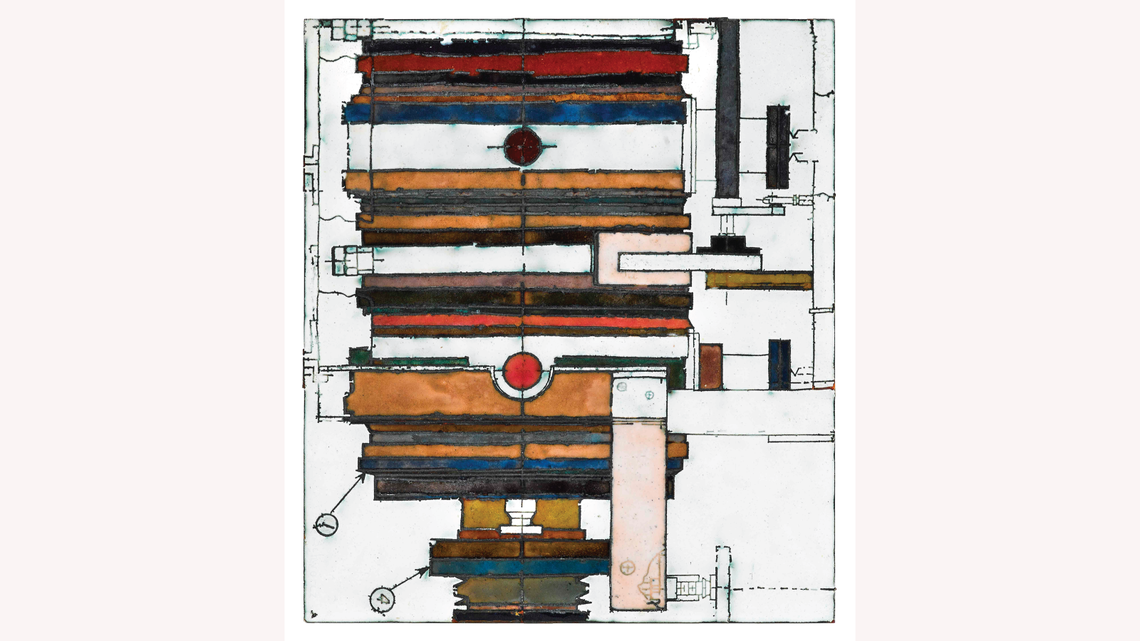

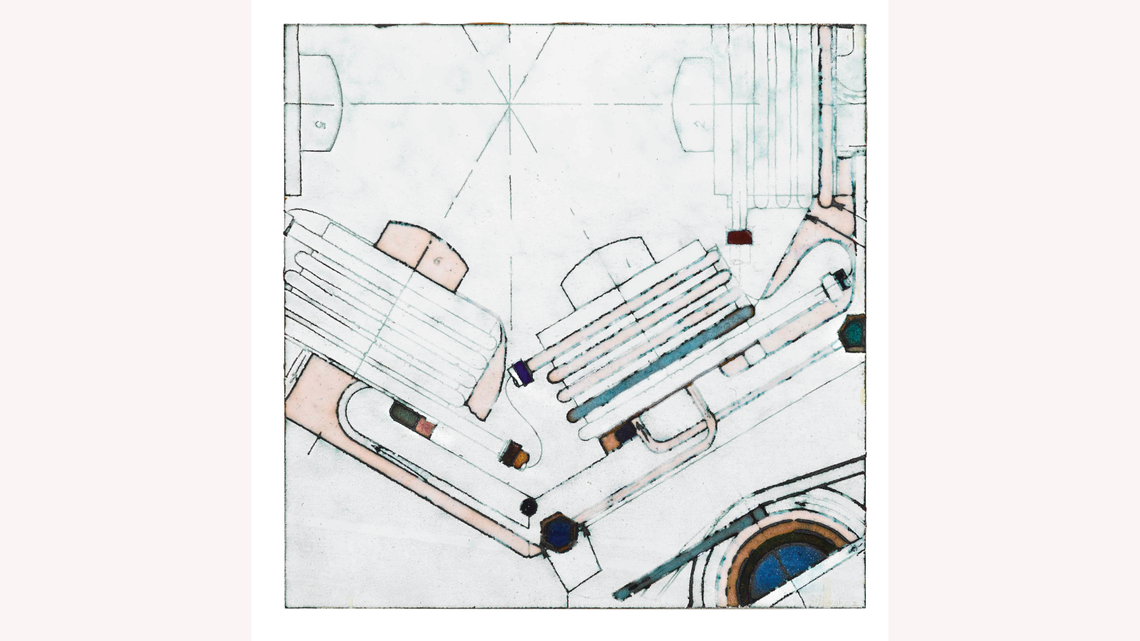

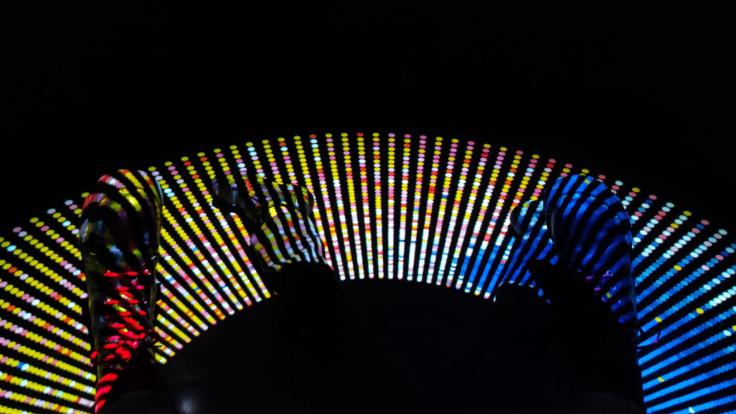

Today, works called SLAC Drawing III, VII and VIII, created in 1974 and 1975 from electroplated copper and enamel, form a unique part of a retrospective at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Among the richly formed and boldly textured and colored vessels that make up the majority of June’s oeuvre, the SLAC-inspired panels stand out for their fidelity to the mechanical design of their inspiration.

The description next to the display at the gallery describe the “SLAC Blueprints” as resembling “ancient pictographs drawn on walls of a cave or glyphs carved in stone.” The designs appear to depict accelerator components, such as electromagnets and radio frequency structures.

According to Harold B. Nelson, who curated the exhibit with Bernard N. Jazzar, “The panels are quite unusual in the subtle color palette she chose; in her use of predominantly opaque enamels; in her reliance on a rectilinear, geometric format for her compositions; and in her reference in the work to machines, plans, numbers, and mechanical parts.

“We included them because they are extremely beautiful and visually powerful. Together they form an important group within her body of work.”

Making history

June and Leroy Schwarcz met in the late 1930s and were married in 1943. Two years later they moved to Chicago where Leroy would become chief mechanical engineer for the University of Chicago’s synchrocyclotron, which was at the time the highest-energy proton accelerator in the world.

Having studied art and design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn several years earlier, June found her way into a circle of notable artists in Chicago, including Bauhaus legend László Moholy-Nagy, founder of Chicago’s Institute of Design.

Around 1954, June was introduced to enameling and shortly thereafter began to exhibit her art. She and her husband had two children and relocated several times during the 1950s for Leroy’s work. In 1958 they settled in Sausalito, California, where June set up her studio in the lower level of their hillside home.

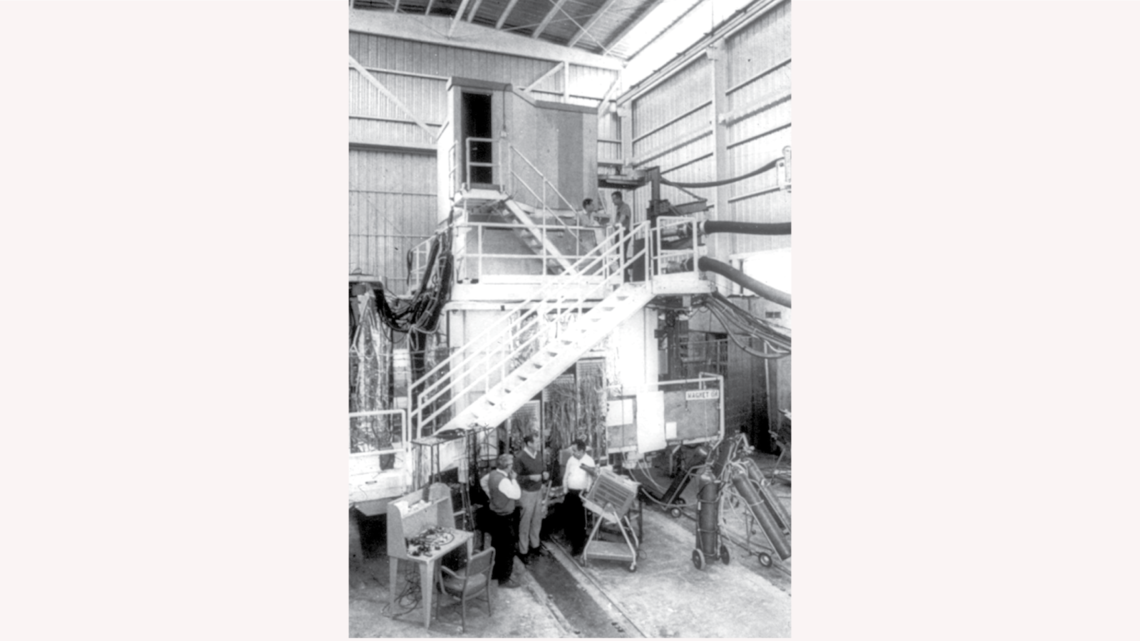

In 1961, Leroy became the first mechanical engineer hired by Stanford University to work on “Project M,” which would become the famous 2-mile-long linear accelerator at SLAC. He oversaw the engineers during early design and construction of the linac, which eventually enabled Nobel-winning particle physics research.

June and Leroy’s daughter, Kim Schwarcz, who made a living as a glass blower and textile artist until the mid 1980s and occasionally exhibited with her mother, remembers those early days at the future lab.

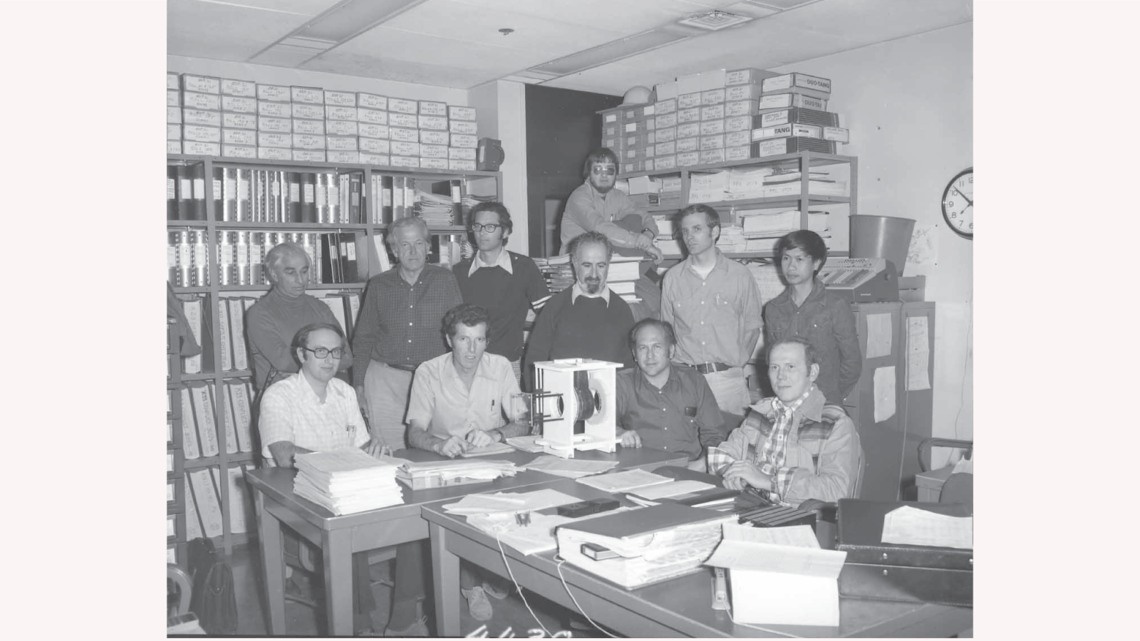

“Before SLAC was built, the offices were in Quonset huts, and my father used to bring me down, and I would bicycle all over the campus,” she recalled. “Pief was a family friend and so was Bob Mozley. Mom introduced Bob to his future wife…It was a small community and a really nice community.”

W.K.H. “Pief” Panofsky was the first director of SLAC; he and Mozley were renowned SLAC physicists and national arms control experts.

Finding beauty

Kim was not surprised that her mother made art based on the SLAC drawings. She remembers June photographing the foggy view outside their home and getting inspiration from nature, ethnic art and Japanese clothing.

“She would take anything and make something out of it,” Kim said. “She did an enamel of an olive oil can once and a series called Adam’s Pants that were based on the droopy pants my son wore as a teen.”

But the fifteen SLAC-inspired compositions were unique and a family favorite; Kim and her brother Carl both own some of them, and others are at museums.

In a 2001 oral history interview with the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art, June explained the detailed work involved in creating the SLAC drawings by varnishing, scribing, electroplating and enameling a copper sheet: “I'm primarily interested in having things that are beautiful, and of course, beauty is a complicated thing to devise, to find.”

Engineering art

Besides providing inspiration in the form of technical drawings, Leroy was influential in June’s career in other ways.

Around 1962 he introduced her to Jimmy Pope at the SLAC machine shop, who showed June how to do electroplating, a signature technique of her work. Electroplating involves using an electric current to deposit a coating of metal onto another material. She used it to create raised surfaces and to transform thin sheets of copper—which she stitched together using copper wire—into substantial, free-standing vessel-like forms. She then embellished these sculptures with colored enamel.

Leroy built a 30-gallon plating bath and other tools for June’s art-making at their shared workshop.

“Mom was tiny, 5 feet tall, and she had these wobbly pieces on the end of a fork that she would put into a hot kiln. It was really heavy. Dad made a stand so she could rest her arm and slide the piece in,” Kim recalls.

“He was very inventive in that way, and very creative himself,” she said. “He did macramé in the 1960s, made wooden spoons and did scrimshaw carvings on bone that were really good.”

Kim remembers the lower-level workshop as a chaotic and inventive space. “For the longest time, there was a wooden beam in the middle of the workshop we would trip over. It was meant for a boat dad wanted to build—and eventually did build after he retired,” she said.

At SLAC Leroy’s work was driven by his “amazingly good intuition,” according to a tribute written by Mozley upon his colleague’s death in 1993. Even when he favored crude drawings to exact math, “his intuitive designs were almost invariably right,” he wrote.

After the accelerator was built, Leroy turned his attention to the design, construction and installation of a streamer chamber scientists at SLAC used as a particle detector. In 1971 he took a leave of absence from the California lab to go back to Chicago and move the synchrocyclotron’s 2000-ton magnet from the university to Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

“[Leroy] was the only person who could have done this because, although drawings existed, knowledge of the assembly procedures existed only in the minds of Leroy and those who had helped him put the cyclotron together,” Mozley wrote.

Beauty on display

June continued making art at her Sausalito home studio up until two weeks before her death in 2015 at the age of 97. A 2007 video shows the artist at work there 10 years prior to her passing.

After Leroy died, her own art collection expanded on the shelves and walls of her home.

“As a kid, the art was just what mom did, and it never changed,” Kim remembers. “She couldn’t wait for us to go to school so she could get to work, and she worked through health challenges in later years.”

The Smithsonian exhibit is a unique collection of June’s celebrated work, with its traces of a shared history with SLAC and one of the lab’s first mechanical engineers.

“June had an exceptionally inquisitive mind, and we think you get a sense of the rich breadth of her vision in this wonderful body of work,” says curator Jazzar.

June Schwarcz: Invention and Variation is the first retrospective of the artist’s work in 15 years and includes almost 60 works. The exhibit runs through August 27 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Renwick Gallery.

Editor's note: Some of the information from this article was derived from an essay written by Jazzar and Nelson that appears in a book based on the exhibition with the same title.